After a log was hewn square with an axe, and if someone wanted lumber for joists, flooring, or siding, the timber would then be taken to a pit saw.

Operating a human powered saw is much more labor intensive than swinging an axe. I have found that it only takes a few strokes of the saw before the first time user has had quite enough. Never volunteer to be the man under the timber, you do not want to be the person at the bottom of this pit who is showered upon with sawdust all day.

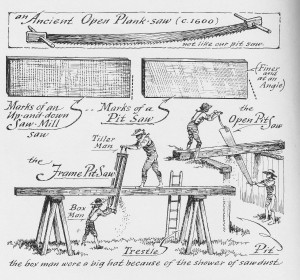

Notice the saw patterns that this form of cutting lumber creates.

When salvaging a house this is often a great indicator of the age of the home. Circular saws came into existence around 1800 (which of course created circular patterns). The type of saw pattern seen on a houses framing members can clue a person in as to which side of that century mark the home is from.

The appreciation for these vertical markings on lumber leads “old house guys” today to seek out new lumber (when it is needed) from sawmills that cut their lumber with band-saw mills which create similar vertical markings to that of the 18th century and earlier.

Often squared timbers were taken to a pit saw and these hewn members would be sawn into three ceiling joists. This would create one joist which would have sawn marks on two sides, and two joists that would each have a sawn face on one side and an axe hewn face on the other. It’s a treat to go into an 18th century house and spot this two to one ratio. I’ve pointed this feature out to both architectural historians and tour guides who had never heard of this.

This sketch is from Eric Sloane’s book “Museum of Early American Tools” which is one the books on my recommended reading list (the link to which can be found on the home page). This will be my last posting of Sloane’s sketches. I hope you have enjoyed them.

Originally posted 2015-08-08 13:07:02.